unbundling suicide thoughts: how to think and talk about them

suicide, and how we would deal with it

Author's note: This blog post discusses the topic of suicide, which may be distressing for some readers. If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, please reach out for help.

Estimated reading time: 25 minutesSuicide.

A beautiful word.

A word that carries the weight of unimaginable pain, often spoken in hushed tones and shrouded in taboo. Just the perfect topic to discuss with your friends and family.

More than 700,000 people die due to suicide every year. For every suicide recorded, there are many more people who attempted suicide.

Behind every statistic, there is a person—a life cut short, a potential unfulfilled, a story left incomplete. Today, we confront this shadow that looms over so many lives, bringing it out of the darkness and into the light.

In our fast-paced world, where we are more connected than ever yet often feel profoundly isolated, the struggle within our minds is a silent epidemic. Suicide is not a mere act; it is the final nail in the coffin, the symptom of a battle fought in silence, a war against invisible demons that many face alone. It affects people from all walks of life, leaving behind a wake of grief, confusion, and unanswered questions for those left behind.

This post is not just a collection of words—it is a plea for awareness and an invitation for empathy. We will explore the complexities of suicide, understand its roots, and, most importantly, see suicide in a deeper view. Probably slightly different from what’s usually discussed on the topic.

I’m not speaking against suicide nor for it. In this post, I would really like to talk about how we, despite our advances in society and technology, are still struggling with how to handle this odd desire of a human - the desire to die.

1. would you kill (for) your family?

William Dresser cherished his wife, Frances, deeply.

Yet, Frances Dresser longed for relief from her suffering.

An unfortunate accident paralyzed her frail body. She had endured countless surgeries and endless pain. Her condition had deteriorated to the point where each day was a struggle, marked by relentless suffering. Doctors had given her little hope of recovery, estimating that she had only a short time left, a time filled with unbearable agony. As she lay in her hospital bed, her husband watched helplessly, seeing the woman he loved in constant distress. Frances wanted peace now. Her pleas for release from her torment echoed in William's mind.

Eventually, William, unable to bear the sight of his beloved wife's suffering any longer, took a pistol and four bullets, two for his wife, two for him, went to the hospital, and ended Frances's life.

Rapid and dramatic developments in medicine and technology have given us the power to save more lives than was ever possible in the past. Medicine has put at our disposal the means to cure or reduce the suffering of people afflicted with diseases that were once fatal or painful.

At the same time, however, medical technology has given us the power to sustain the lives (or, some would say, prolong the deaths) of patients whose physical and mental capabilities cannot be restored, whose degenerating conditions cannot be reversed, and whose pain cannot be eliminated. As medicine struggles to pull more and more people away from the edge of death, the plea that tortured, deteriorated lives be mercifully ended grows louder and more frequent.

When William performs the act of killing Frances, he brings about the death of his wife because he believes the latter’s present existence is so bad that she would be better off dead. Accordingly, the motive of the person who performs an act of euthanasia is to benefit the one whose death is brought about.

William was still, tried for murder. He himself was put under suicide watch.

no way of “helping” with suicide is created equally

No way of “helping” with suicide is created equally. It has many layers, each with its own set of moral problems. So, to understand them more easily, let’s break it down to this story:

Imagine you're stuck with a book so bad that you just can't take it anymore. You could either ask your friend to pass you a set of matches so you can burn it yourself (assisted suicide) or beg them to set it on fire for you (euthanasia).

In assisted suicide, it's you're given the matches and lighter fluid, but it's your hand that strikes the match. You're in control, deciding when and how to end the misery. A physician or friend might hand you the tools, but you're the one who decides to use them. This method is legally and ethically murky, with some places like Switzerland and a few progressive states in the U.S. saying, "Go ahead, burn that book yourself if you must."

Youth in Asia, on the other hand, is when you hand over the book and matches to someone else and say, "Please, just end this torture for me." Here, a third party—usually a physician—takes on the responsibility of putting both of you and the book out of its misery. They might do this because you've asked them to (voluntary euthanasia), because you can't ask but it's obvious you hate every page (non-voluntary euthanasia), or against your wishes, which no one thinks is okay (involuntary euthanasia). Countries like the Netherlands, Belgium, and Canada have said, "Fine, but we need a list of rules and conditions to make sure this isn't just an impulsive book burning."

So, the main difference?

Control.

In assisted suicide, you strike the match; in euthanasia, someone else does it for you. While both scenarios are contentious and fraught with legal and ethical debates, euthanasia usually gets more side-eye because someone else is lighting the match, which is unhelpfully similar to murder.

Californians are now being asked to support an initiative, entitled the Humane and Dignified Death Act, which would allow a physician to end the life of a terminally ill patient upon the request of the patient, pursuant to properly executed legal documents. Under present law, suicide is not a crime, but assisting in suicide is. Whether or not we as a society should pass laws sanctioning "assisted suicide" has generated intense moral controversy.

Supporters of legislation legalizing assisted suicide claim that all persons have a moral right to choose freely what they will do with their lives as long as they inflict no harm on others. This right of free choice includes the right to end one's life when one chooses. For most people, the right to end one's life is a right they can easily exercise.

But there are many who want to die, but whose disease, handicap, or condition renders them unable to end their lives in a dignified manner. When such people ask for assistance in exercising their right to die, their wishes should be respected.

It is argued, we ourselves have an obligation to relieve the suffering of our fellow human beings and to respect their dignity. Lying in our hospitals today are people afflicted with excruciatingly painful and terminal conditions and diseases that have left them permanently incapable of functioning in any dignified human fashion. They can only look forward to lives filled with yet more suffering, degradation, and deterioration.

When such people beg for a merciful end to their pain and indignity, it is cruel and inhumane to refuse their pleas. Compassion demands that we comply and cooperate.

Those who oppose any measures permitting assisted suicide argue that society has a moral duty to protect and to preserve all life. To allow people to assist others in destroying their lives violates a fundamental duty we have to respect human life. A society committed to preserving and protecting life should not commission people to destroy it.

Further, opponents of assisted suicide claim that society has a duty to oppose legislation that poses a threat to the lives of innocent persons. And, laws that sanction assisted suicide inevitably will pose such a threat. If assisted suicide is allowed on the basis of mercy or compassion, what will keep us from "assisting in" and perhaps actively urging, the death of anyone whose life we deem worthless or undesirable? What will keep the inconvenienced relatives of a patient from persuading him or her to "voluntarily" ask for death? What will become of people who, once having signed a request to die, later change their minds, but, because of their conditions, are unable to make their wishes known?

And, once we accept that only life of a certain quality is worth living, where will we stop? When we devalue one life, we devalue all lives. Who will speak for the severely handicapped infant or the senile woman?

It is now well-established in many jurisdictions that competent patients are entitled to make their own decisions about life-sustaining medical treatment. That is why they can refuse such treatment even when doing so is tantamount to deciding to end their life. It is plausible to think that the fundamental basis of the right to decide about life-sustaining treatment – respect for a person’s autonomy and her assessment of what will best serve her well-being – has direct relevance to the legalization of voluntary euthanasia.

In consequence, extending the right of self-determination to cover cases of voluntary euthanasia does not require a dramatic shift in legal policy. Nor do any novel legal values or principles need to be invoked. Indeed, the fact that suicide and attempted suicide are no longer criminal offences in many jurisdictions indicates that the central importance of individual self-determination in a closely analogous context has been accepted.

The fact that voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide have not been more widely decriminalized is perhaps best explained along a similar line to the one that has frequently been offered for excluding the consent of the victim as a justification for an act of killing, namely the difficulties thought to exist in establishing the genuineness of the consent.

But, the establishment of suitable procedures for giving consent to voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide is surely no harder than establishing procedures for competently refusing burdensome or otherwise unwanted medical treatment. The latter has already been accomplished in many jurisdictions, so the former should be achievable as well.

Finally, it is argued that sanctioning assisted suicide would violate the rights of others. Doctors and nurses might find themselves "pressured" to cooperate in a patient's suicide. To satisfy the desires of a patient wanting to die, it's unjust to demand that others go against their own deeply held convictions.

Suppose that the moral case for legalizing voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide does come to be judged more widely as stronger than the case against legalization, and they are made legally permissible in more jurisdictions than at present. Should doctors take part in the practice? Should only doctors perform voluntary euthanasia? These questions ought to be answered in light of the best understanding of what it is to provide medical care.

The proper administration of medical care should promote the welfare of patients while respecting their individual self-determination. It is these twin values that should guide medical care, not the preservation of life at all costs, or the preservation of life without regard to whether patients want their lives prolonged should they judge that life is no longer of benefit or value to them. Many doctors in those jurisdictions where medically assisted death has been legalized and, to judge from available survey evidence, in other liberal democracies as well, see the practice of voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide as not only compatible with their professional commitments but also with their conception of the best medical care for the dying.

That being so, doctors of the same conviction in jurisdictions in which voluntary medically assisted death is currently illegal should no longer be prohibited by law from lending their professional assistance to competent terminally ill persons who request assistance with dying because of irremediable suffering or because their lives no longer have value for them.

2. would you tell a stranger to kill themselves?

How would you talk to a person who’s having a suicidal thought?

Well, I'm almost absolutely certain that none of my moral readers reading this will think by themselves,

"I would encourage him to follow through with it".

When someone confides to us that they are having suicidal thoughts, our first instinct is the urgent desire to help.

How can we not want to help them, to talk them out of this suicidal thought? Because we, even as strangers, care about each other’s wellbeing. We, as a species, have evolved ourselves and society for the sole purpose of sustaining ourselves. So the idea of giving up on the pursuit, on life, seems alien, seems puzzling.

How could anyone nurture such audacious thought?

In our haste to intervene, we might inadvertently overlook or downplay the depth and complexities of their emotions, potentially making them feel misunderstood or guilty for sharing their struggles.

This is not rare. It is so not rare that so many people who have gone suicidal decide to shut down on sharing with their close circle before even uttering a word. This well-intentioned but misguided response can drive them to seek outside help from someone who understands their problems but with less emotional stake on the matter. Did some say a forum?

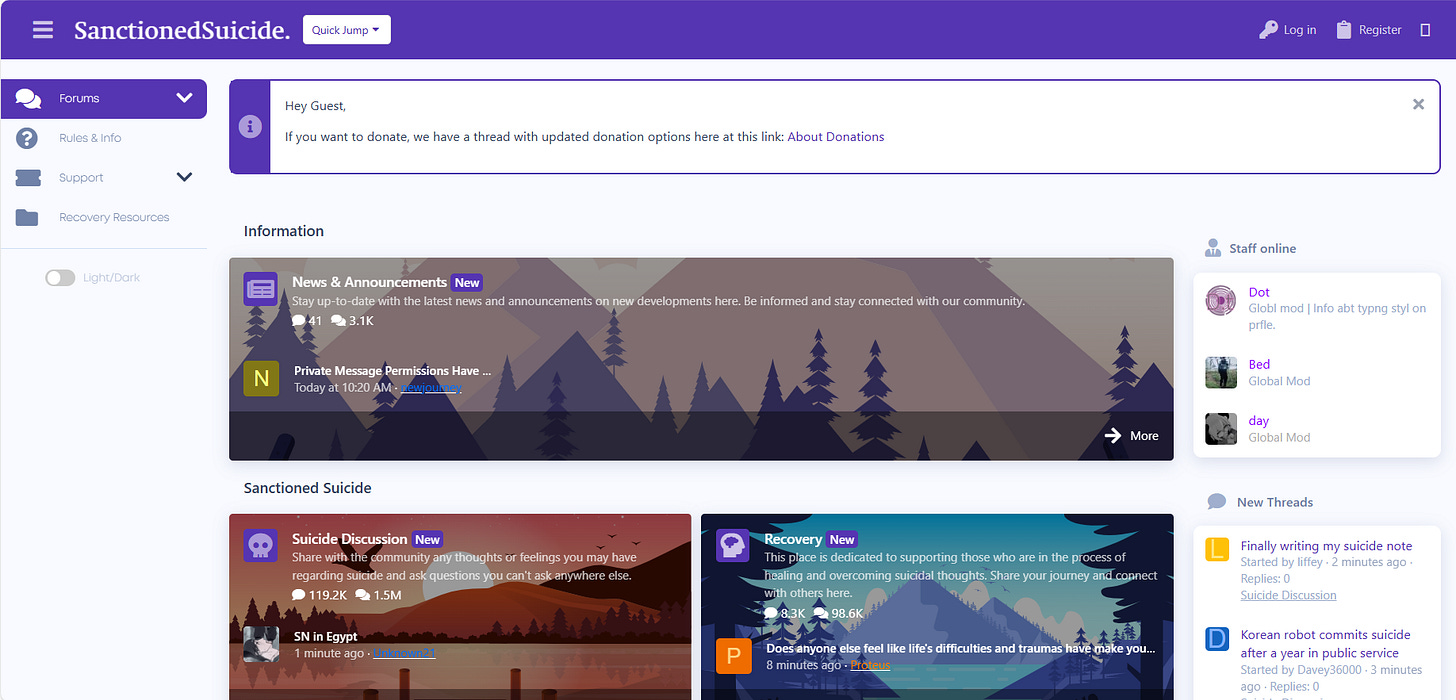

Sanctioned suicide refers to a phenomenon where online communities or websites create an environment that encourages and facilitates discussions about suicide. The main difference with popular social media platforms is that these sites aren’t necessarily against suicide. They describe themselves as a “pro-choice” platform.

The biggest sanctioned suicide forum has more than 40,000 members, with millions of views every month. Concerning? Good. Let’s take a tour.

sanctioned suicide

Welcome to the Sanctioned Suicide Forum, where we've taken the age-old concept of 'support groups' and twisted it. Forget about your friends’ good old guilty trip on the beauty of life and that you need to cherish and hold on to it; here, we specialize in cheering on your darkest thoughts. Feeling down? Well, don't worry, because instead of a pep talk, you'll get a detailed guide on how to check out early.

Let's face it, who needs hope and recovery when you can have a step-by-step tutorial on ending it all? It's like Pinterest for the terminally depressed. But hey, why stop at sharing recipes and craft ideas when you can share the quickest routes to oblivion? It's all the rage now—misery loves company, after all.

The site is divided into three forums: Recovery, Suicide Discussion, and Off-topic. The Recovery forum is where you’ll find the rare souls trying to find a glimmer of hope amidst the darkness—bless their hearts. The Suicide Discussion forum, on the other hand, is like a how-to manual, featuring detailed discussions on methods and a good ol' pat on the back for anyone looking to "catch the bus" (a quaint little euphemism for committing suicide). And let’s not forget the Off-topic forum, where you can chat about hobbies and daily life, because, hey, why not mix a little small talk with your death planning?

The Suicide Discussion forum is the most popular. It's the place to be if you want a thorough breakdown of the most efficient ways to end it all, peppered with casual encouragement from your fellow travelers on this morbid journey. It's like a macabre support group, but instead of cheering you on to overcome your struggles, they’re all about helping you make a swift exit.

Okay, that ends our tour. Now let’s ask the real question:

Has the forum encouraged people to act on their suicidal thoughts, actually?

Matthew van Antwerpen, a 17-year-old from suburban Dallas, got really down last year with the struggles of remote schooling during the pandemic. Desperate, he found a website about suicide. He posted, “Any enjoyment or progress I make in my life simply comes across as forced. I know it is all just a distraction to blow time until the end.”

Roberta Barbos, a 22-year-old student at the University of Glasgow, first posted after a breakup, saying she was “unbearably lonely.” Shawn Shatto, 25, shared how miserable she felt at her warehouse job in Pennsylvania. Daniel Dal Canto, a 16-year-old from Salt Lake City, expressed his fear that his undiagnosed stomach issues might never get better.

Not long after joining, all four were dead.

Unlike most suicide websites that focus on prevention, this one actually provides detailed instructions on how to end your life.

The four young people were among tens of thousands worldwide who got drawn to this site. In public forums, live chats, and private messages, users talk about methods like hanging, poison, guns, and gas. They even look for partners to meet up and die together. Members cheer each other on, sharing suicide plans and posting supportive messages, emojis, and praise for those who go through with it, calling them “brave,” “a legend,” or “a hero.”

The New York Times identified 45 who had killed themselves across the US, UK, Italy, Canada, and Australia. The actual number of deaths linked to the site is probably much higher.

Over 500 members—more than two a week—posted “goodbye threads” with their plans and then never posted again. Many described their attempts in real-time posts. Some even watched others live-stream their deaths off-site. These “goodbye” threads will be later deleted after some time since the original poster’s last interaction, to cut off any association with the site.

Most users mentioned using a specific preservative for curing meat, which the site has popularized as a method of suicide. This has alarmed coroners and doctors, but many public health and law enforcement officials don’t even know about it.

Dr. Daniel Reidenberg, a psychologist and the executive director of Suicide Awareness Voices of Education, a national nonprofit, said, “It’s disgusting that anyone would create a platform like this. There’s no question that this site, the way they created it, operate it and allow it to continue, is extremely dangerous.”

Countries like Australia, Germany, and Italy have managed to restrict access to the site within their borders. However, American law enforcement officials, lawmakers, and tech companies have been hesitant to act. You can still access the site from places like Vietnam, but it’s not easy.

And when asked to stop steering visitors to the suicide site, the world’s most powerful search engine deflected responsibility. “Google Search holds a mirror up to what is on the internet,” a senior manager for the company wrote to Australian officials in February 2019.

In online posts, Marquis, one of the two founders of the site, repeatedly said that the site complied with U.S. law and did not permit the assisting or encouraging of suicide.

He has several times referred to the site as a “pro-choice” forum that supports members’ decisions to live or to die. “People are responsible for their own actions at the end of the day,” Marquis wrote last year, “and there’s not much we can do about that.”

It came online after Reddit shut down a group where people had been sharing suicide methods and encouraging self-harm. Reddit prohibited such discussion, as did Facebook, Twitter and other platforms. Serge, the other founder, wrote days after the new site opened that the two men had started working on it because they “hated to see the community disperse and disappear.”

On their site, a person could browse a “resource” thread, a table of contents linking to methods that were compiled by members and stretched for dozens of pages. Or they could click on a suicide wiki page with similar instructions. Fellow members often derided therapy and other treatments and encouraged one another to keep their suicidal intentions hidden from relatives and medical professionals.

In posts, Serge and Marquis noted their own struggles.

“Not much to tell about myself except that I’ve never really found a reason to be here,” Serge wrote. “There is little that I find worthy in this life.”

Marquis had been on the brink of suicide at one point, he disclosed. He had concluded that the mental health system “fails everyone” and treats people with problems as “outcasts.”

Explaining the purpose of the site, he wrote, “This community was made as a place where people can freely speak about their issues without having to worry about being ‘saved’ or giving empty platitudes.”

While some of those drawn to the website described suffering from physical pain, most mentioned depression, bipolar disorder or other mental illnesses.

About half were 25 or younger, a survey on the forum showed; some were minors.

For many people, suicidal thoughts will eventually pass, experts say. Treatment and detailed plans to keep safe can help. However, clinicians and researchers warn that people are much more likely to attempt suicide if they learn about methods and become convinced that it’s the right thing to do. The suicide site facilitates both.

While there is discussion on the site about not giving up hope and the merits of staying alive, there is much more about the reasons to die. Among the most viewed posts, for example, are the “goodbye threads.”

In the site’s written rules, assisting and encouraging suicide were prohibited, while providing “factual information” and “emotional support” was not. In practice, some members urged others on, whether with gentle reassurance or with more force.

Links to a suicide hotline and other mental health resources appeared on the site, as did a new public forum focusing on recovery from suicidal thoughts. But Marquis also noted that people who registered only to use the recovery forum “will be denied most likely.”

As several deaths drew scrutiny from news organizations, he claimed that critics wanted “total annihilation of this website,” dismissed coverage as “the usual pro-life BS” and vowed to take “drastic measures” — going to court — to stop efforts to take it down.

“They’ll never prevail with censorship and we will fight every one of their attempts to do so,” Marquis wrote.

His fierce defense drew praise from members. Many said the site was a rare safe space to share their feelings. Some said it had helped them realize they did not want to die.

Asked about the website, a Google spokeswoman, Lara Levin, said, “This is a deeply painful and challenging issue.” In a written statement, she said Google tried to help protect vulnerable users, including ensuring that suicide hotlines are visible. But, she said, “we balance these safeguards with our commitment to give people open access to information.”

And because suicide is no longer considered a crime, as it was for centuries, the police see little reason to investigate it, whether they were encouraged, or even assisted.

The popularity of the "Sanctioned Suicide" forum can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the anonymity it offers allows users to discuss their suicidal ideations without fear of judgment or immediate intervention. This can be particularly appealing to individuals who have faced stigma or dismissal when seeking help in more traditional settings, like their family, circle of friends, or even hotlines.

Additionally, the forum's unique philosophy on what should be censored and what should not, in addition to its community-driven ethos, creates an environment where users can share explicit details about their experiences and methods. This can provide a sense of validation and solidarity for those feeling isolated in their suffering. Sanctioned Suicide offers a form of companionship in despair, where users can find others who understand their pain and are willing to listen without the intent to dissuade or intervene.

However, the very nature of this site is what makes it profoundly troubling and dangerous. Unlike support groups aimed at recovery and prevention, the "Sanctioned Suicide" forum often perpetuates a fatalistic outlook on life, sometimes even providing practical advice on how to carry out self-harm or suicide. This creates an echo chamber where vulnerable individuals can be pushed further into their despair rather than finding a path to healing. Reports have emerged of users who have acted on the advice given on these forums, leading to tragic and irreversible outcomes.

The opinions surrounding this site are deeply divided.

Mental health professionals and advocacy groups are alarmed by the existence of such communities, arguing that they represent a significant public health risk. They emphasize the need for stricter regulations to monitor and potentially shut down sites that promote self-harm and suicide. Critics assert that these forums exploit the vulnerable and can act as catalysts for individuals on the brink of making life-ending decisions, thereby bypassing critical opportunities for intervention and support.

Conversely, some argue that such forums provide a necessary outlet for free speech and that individuals should have the right to discuss their experiences openly, even if those discussions include suicide. They contend that the focus should be on improving mental health services to offer better support and reduce the number of people who feel driven to these sites in the first place.

Ultimately, the existence and popularity of the "Sanctioned Suicide" forum underscore a significant and urgent gap in mental health support systems. The site’s chilling success points to the need for more accessible, compassionate, and effective mental health care. It also highlights the importance of societal efforts to destigmatize mental health issues, ensuring that those in need feel safe and supported in seeking help. This complex and multifaceted issue demands a comprehensive response that balances compassion, support, and regulation to protect the most vulnerable among us.

It is tempting to deem Sanctioned Suicide as a force of evil. But let’s rethink about the root question, which is:

3. is suicide… even bad?

Imagine a friend of yours, let's call her Lisa (if you have an actual friend named Lisa please tell her I’m not talking about her), is contemplating suicide hard.

She has not told anyone about her thoughts yet. But for the sake of the conversation, let’s just say some omniscient philosophers are noticed.

Now, some of them argue that Lisa should be allowed to make this decision if she has thought it through rationally and logically. Kantians, who follow the ideas of the philosopher Kant, add that if Lisa is making this choice based on reasons she finds important, we should respect her decision. This is different from the libertarian viewpoint, which says anyone can choose suicide for any reason and nobody else should interfere. You know, because of autonomy.

Here's where it gets tricky: some others believe that choosing to end your own life is always irrational because you can't compare being alive to being dead since, well, we don’t really know what being dead is like (heaven? hell? afterlife? just go dark?).

But more recent thinking says we should compare two possible futures for Lisa: one where she ends her life and one where she continues living. Classic trolley problem! Richard Brandt, a philosopher, says Lisa is weighing her future options—like picking between a shorter, steeper path and a longer, winding one.

Philosophers have come up with specific conditions to determine when a decision to die is rational. These conditions are split into two categories:

cognitive conditions (making sure Lisa’s thought process is clear and informed)

interest conditions (making sure ending her life fits her long-term interests).

For instance, Glenn Graber says suicide can be rational if Lisa makes a calm and clearheaded assessment that shows she’d be better off dead. Margaret Battin lists a few more criteria like the ability to reason causally, having a realistic view of the world, and having enough information relevant to the decision.

Even if Lisa doesn’t show obvious signs of irrationality or legal insanity, her decision might not be rational. Sometimes, people decide to commit suicide impulsively, influenced by mental illnesses like depression. Think of it like making a huge life decision when you're really drunk—not exactly the best time for clear thinking. Suicidal people might not fully grasp how final death is, or they might have grandiose ideas about the impact of their death, like thinking it will make them a martyr.

The link between mental illness and suicidal behavior is complicated. While many suicidal individuals have symptoms of depression, not everyone with depression attempts suicide, nor even thinks of it (guess who?). This means other factors are at play. Just because someone has a mental illness doesn’t mean they’re irrational or incapable of making their own decisions. But the connection often leads to judgments that those contemplating suicide have 'disordered' minds, which might not always be fair.

shouldn’t we tie up the suicidal?

Most moral viewpoints agree that it’s okay to try and stop Lisa under certain circumstances, even recommend to do so. Non-coercive actions—like talking to her, trying to convince her life is worth living, or recommending she see a therapist—are generally seen as good moves since they respect her autonomy and rational thinking.

But what about more forceful measures, like restraining Lisa physically or getting her institutionalized? Now that’s controversial. Given that suicidal impulses are often fleeting and influenced by mental illness, it might be justifiable to intervene on ‘soft’ paternalist grounds. This is the “better safe than sorry” approach. It’s better to stop Lisa temporarily and sort things out with professional help than to let her make an irreversible decision in a moment of crisis, or as someone said before “find a permanent solution to a temporary problem”.

The ethics of suicide prevention vary depending on how and where the intervention happens. Stopping someone in a clinical or legal setting is different from answering calls on a suicide hotline, which raises different concerns about rights, privacy, and trust. Preventive measures like restricting access to means of suicide (like firearms or poisons) raise even more questions about the effectiveness and the impact on people who aren't suicidal.

Finally, if we sometimes have a duty to prevent suicide, it makes us wonder if it’s ever okay or even necessary to help someone end their life. Critics worry about a ‘slippery slope’ where assisted suicide becomes so common that vulnerable people might be pressured into it for others' benefit. Imagine an elderly person feeling pushed into suicide because their family or caregivers find it convenient. However, studies from places where assisted suicide is legal don’t fully support these fears, suggesting we need to handle the issue with care and strict regulations.

Every year there are 700,000 people committed suicide. That’s one person every 40 seconds. So based on this number, since the time you started reading this post, there are probably 37 people has just decided to kill themselves, and succeeded. There are way many more people contemplating suicide.

Those might include someone you know.

If you're feeling like there's no way out, please know there is hope. There are and there will be people who care about you. Many individuals who have felt like you do now have found a way to live a fulfilling way. You are not alone in this thing we call life.

Remember, seeking help is a sign of strength. Please onsider reaching out to a trusted friend, family member, or mental health professional. Your life is valuable, and there is hope even when it feels like there is none.

You matter, and there is a path forward, even if it’s hard to see right now.

This is a long and arduous yet worth-contemplating post.

There's a part that struck me the most: "once we accept that only life of a certain quality is worth living, where will we stop? When we devalue one life, we devalue all lives. Who will speak for the severely handicapped infant or the senile woman?"

It reminds me not only of not only suicide or assisted suicide but also of the kind of "assisted suicide" made to a disabled child who has yet to come to life. Non-invasive Prenatal Testing, they say, but a more common definition is "learning if a child is disabled by birth; if yes, parents should "free their child" from suffering life even before it begins". If we deny the disabled child the right to live, we are also denying the currently living disabled people (some of whom might be our "invisibly" disabled friends) the right to live.

Suffering is suffering, that is my view as a non-disabled human body. But whether suicide is the appropriate solution to a specific suffering should be treated with consideration. Before making the decision, I think it's necessary that people be informed to know and understand that suicide is neither superior nor inferior to sustaining a suffering life, or other options; it is ONE of the many possibilities.