8 billion boiling frogs

in your dream home, would there be an air conditioner?

Estimated reading time: 12 minutesWhen I was a kid, air conditioning was a rare luxury in my hometown. Only the richest families could afford one. For the rest of us, me and you fellow peasants, enduring the heat meant finding creative ways to stay cool: kids would rush to buy ice cream from the neighborhood vendor, adults brewed pitchers of ice tea, and the constant hum of electric fans filled our homes. Some would take multiple cold showers a day, seeking any relief from the blazing sun.

Now, a totally different story. Almost every household has at least one air conditioner. Every coffee shop, every store, and every building has AC units installed. The summers have grown so unbearable that surviving without AC seems impossible. When searching for a room to rent in Sài Gòn, it was an absolute must for the room to already have an AC unit installed. The thought of enduring a summer without it was unthinkable; without AC, I knew I would go feral as the temperatures soared.

Air conditioning has transformed from a symbol of luxury to a necessity.

a boiling world

The weather, already hot, has been getting progressively hotter.

It's not uncommon to see people donning layers of clothes and other protective gear when stepping outside, where the streets feel as scorching as a Yangzhou fried rice pan. The last couple of summers have been exceptionally extreme, surpassing normal, bearable conditions. Sài Gòn is currently enduring its longest heat wave in 30 years.

We deal with hot days all the time, and they’re usually uncomfortable at worst. We wear light clothes, stand in the shade, fan ourselves, and commiserate. Our bodies always try to regulate themselves at around 37 degrees Celsius.

When it’s too hot, we produce sweat, and heat is absorbed as it turns into vapor. However, the effects of heat are almost impossible to detect without the proper tools, and the line between discomfort and danger can be hard to detect.

When the air becomes hotter than the body, the skin stops radiating heat and starts absorbing it. If humidity is high, sweat can’t evaporate into the already saturated air. Your body will fail to regulate itself in these extreme yet not uncommon conditions. If you exert yourself, your core temperature will start to climb, and your body will struggle to bring it down.

Discomfort turns into fatigue, nausea, and disorientation. Our heads ache like crazy, the world feels upside down, and our muscles cramp. At that point, the body is experiencing hyperthermia. If its temperature isn’t brought down soon enough, organs fail, and death follows.

Despite being among the deadliest natural disasters, heat waves often go unnoticed. They occur invisibly and leave no tangible wreckage behind. Their lethality is often indirect, exacerbating existing health conditions and revealing their full toll only through later statistical analysis.

Access to cooling often falls along class lines. The homes of the wealthiest are extravagantly cooled, with air conditioners installed in every room, including the toilet. Meanwhile, many people have no access to cooling at all. The poorer you are, the more liable you are to the deadly effects of heat waves, and the more you suffer.

Heat waves disproportionately affect the most vulnerable and marginalized populations: the elderly, those already ill, socially isolated individuals without support networks, and the working poor, who must labor in sweltering conditions or risk going without food. That could be someone’s brother shipping food under the sun. That could be someone’s uncle doing construction work at noon. That could be you and me.

While hospitals have begun expanding their capacity with heat wards, prolonged heat waves could overwhelm these resources. Additionally, while those who can afford it seek refuge in air-conditioned spaces, the poor are left to endure the heat while working on construction sites, building roads, or selling goods on scorching streets.

Video: An animation made by NASA showing the effect of climate change over the years.

Seemingly small increases in global average temperatures mask a crucial shift in extremes. What were once uncomfortably hot days are becoming dangerously hot, and dangerously hot days are becoming deadly.

By the end of the century, almost half the people on Earth will face deadly heat and humidity for more than 20 days a year, according to a study by Camilo Mora, a researcher at the University of Hawaii. And that’s the best-case scenario, assuming drastic reductions in carbon emissions. If emissions continue on their current trajectory, three-quarters of humanity will face deadly heat.

air-conditioning is a solution, but not enough

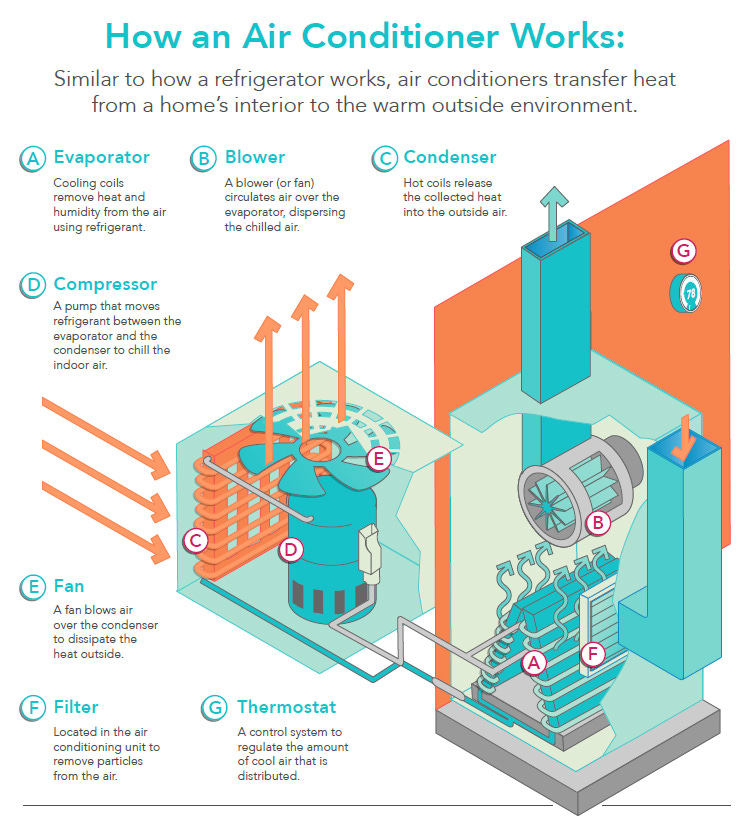

How do air conditioners work?

Imagine your house is like a giant cooler, and an air conditioner is the system that keeps it cool. It works by using a special liquid (refrigerant) that absorbs heat from inside your house. This heat is then pumped outside through a series of coils, releasing the heat outdoors and turning the refrigerant back into a liquid, ready to repeat the process. Fans help blow the cool air inside and push the hot air outside, keeping your home comfortably cool.

The problem with air conditioners is that they don’t actually “condition” the air. It just uses energy and a good amount of refrigerant to bring the heat from indoors to outdoors. The total sum of the game is zero, plus the heat from consuming the energy.

All the new air conditioners are pumping heat out into the streets, raising the temperature for everyone who currently does not have an AC hanging above their heads. And as the earth gets warmer, we will use more air conditioning, which warms us even more. It’s a vicious feedback loop, the only positive thing about it is the temperature rising, which is basically a big FUCK YOU to everyone who can’t afford an AC. If air conditioners become the only way to cope with rising temperatures, this same problematic dynamic will escalate globally.

Across Vietnam, millions of people are deciding they've had enough of the heat. Currently, only about 13 percent of Vietnamese households have air conditioning, but this number is rapidly increasing. Rising incomes are making air conditioners more attainable, while rising temperatures are making them a necessity.

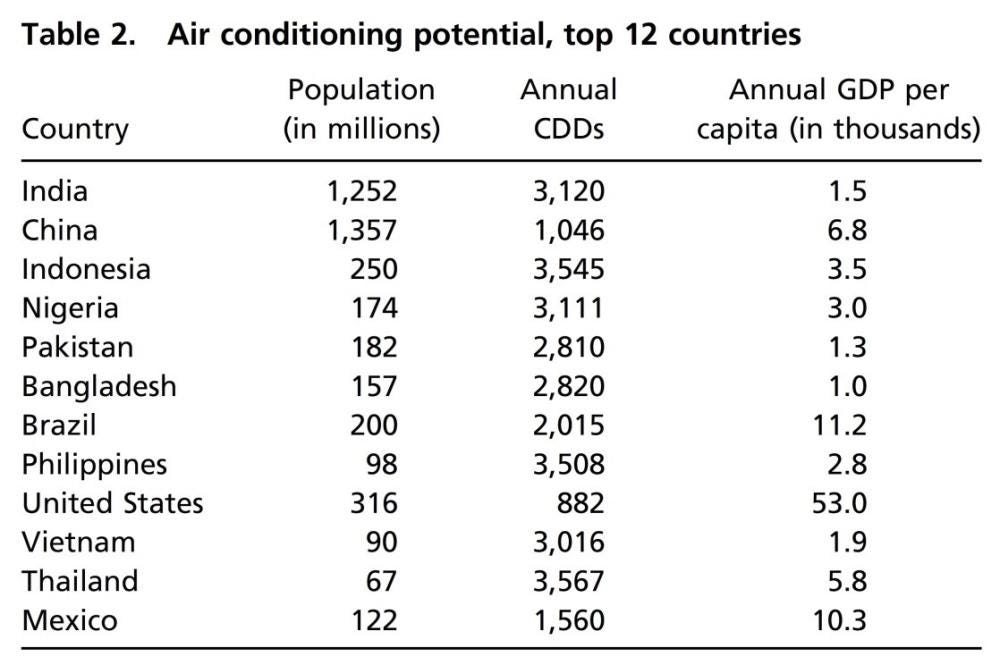

Globally, the world is on track to add 700 million new AC units by 2030 and 1.6 billion by 2050, primarily in hot, developing countries like Vietnam, China, and Thailand. However, this surge in air conditioner usage threatens to exacerbate the very crisis it aims to mitigate and widen the divide between those who can afford to stay cool and those left out in the heat.

Air conditioners use refrigerants, and the most common type—R-410A, or Puron—is a potent greenhouse gas with 1,700 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide, which essentially means that it is 1700 times “better” than carbon dioxide in causing global warming. Luckily, we haven’t mass-produced them ever. Or have we?

If the use of R-410A and similar refrigerants continues to grow at the current rate, these chemicals could account for as much as 19 percent of global emissions by 2050.

Although international initiatives aim to phase down the worst offenders, air conditioners contribute to climate change in another significant way: they consume a tremendous amount of electricity. Managing this growing demand will necessitate the addition of thousands of new power plants to the grid.

Air conditioners may be a double-edged sword, but finding a way to adapt to rising heat is essential. High temperatures are already interfering with people's ability to work, making them sick, and even killing thousands. If heating is considered a basic necessity in a temperate climate, it’s time to start thinking about cooling the same way in a tropical one. A basic level of thermal comfort is necessary to be productive and to sit comfortably in your home at night. Everyone should have access to that level of comfort.

While air conditioners are primarily regarded as comfort appliances, they also play a critical role in saving lives. As air conditioning spread throughout movie theaters, offices, and homes in the 20th-century United States, heat-related deaths plummeted. Without AC, heat and humidity can swiftly become deadly, as was evident this past summer in Asia.

The impending installation of countless new air conditioners has added urgency to the race to make them less damaging to the climate. In 2017, in Kigali, Rwanda, negotiators from 197 countries signed the Kigali Amendment to phase down the use of the most potent greenhouse gas refrigerants—a measure projected to avoid almost a degree of warming by 2100. Between 2020 and 2025, Vietnam has set a target to reduce hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) consumption by 35 percent. Imported HCFC has been reduced to 2,600 metric tons and is expected to be banned in 2040.

Even with increasing efficiency and better refrigerants, the energy demand for air conditioning will remain immense.

Refrigerated cooling initially gained popularity as a method to preserve food, and later for controlling temperature and humidity in factories. Eventually, it was adapted for cooling people. However, it's a blunt instrument and shouldn't be the sole solution. In Vietnamese, we have an idiom “dùng dao mổ trâu để giết gà”, which if translated word-by-word would be “don't use a buffalo-killing knife to slaughter a chicken”. Just as you can't take one pill to cure every illness,. Similarly, a variety of strategies are essential for effectively cooling buildings.

The evaporative cooler, also known as an air cooler or swamp cooler, presents a more cost- and energy-efficient alternative to traditional air conditioners. Instead of using refrigerants, it operates by blowing air over a wetted pad, cooling hot air through evaporation.

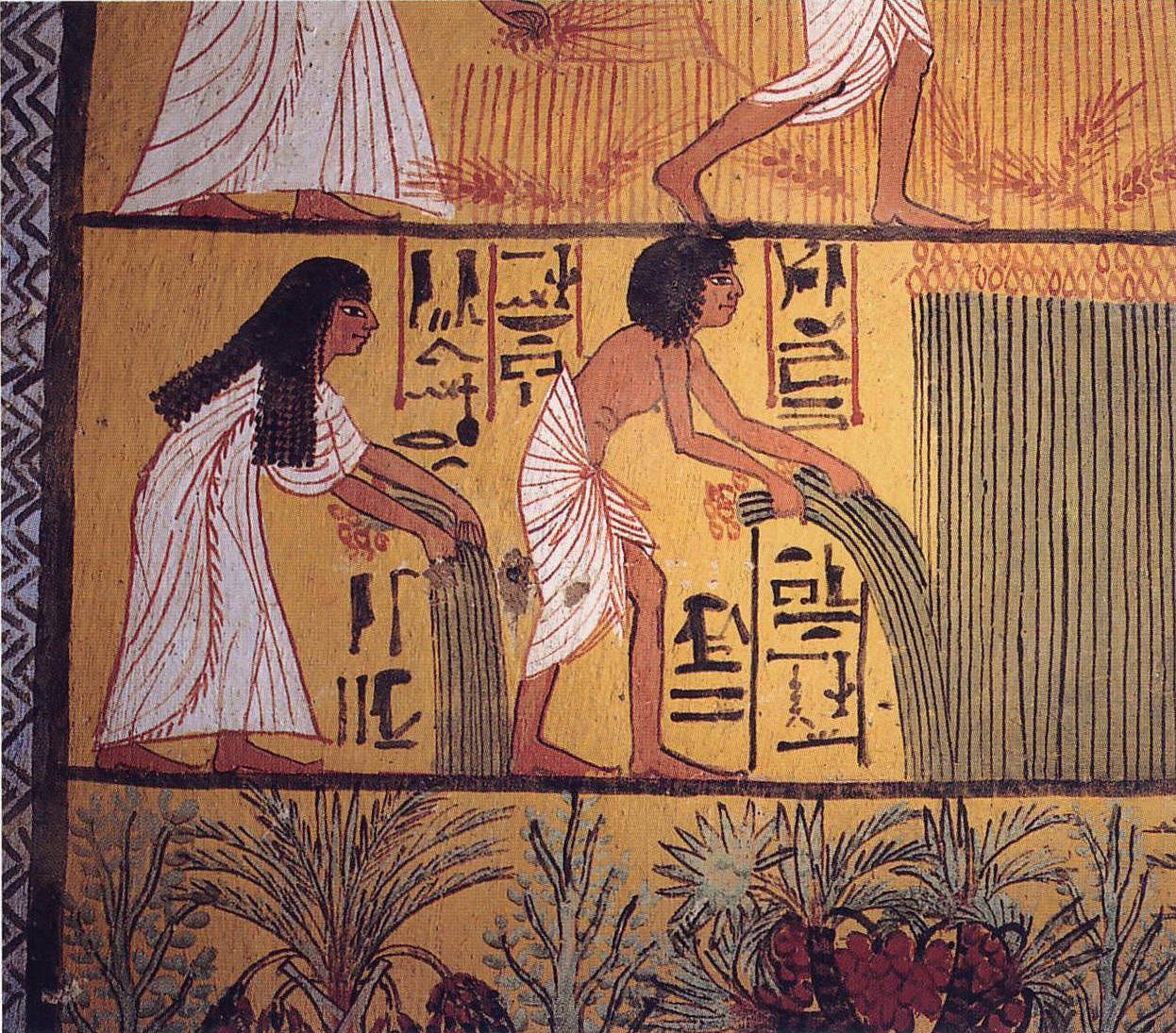

These coolers are cost-effective and consume minimal power, making them accessible to many who cannot afford air conditioners. Additionally, they are relatively easy to set up—simply fill them with water and plug them in. This technology is reminiscent of the method used by ancient Egyptians, who stayed cool by hanging wet reeds on their windows, a practice that was done thousands of years ago.

In regions with generally temperate climates, where installing an air conditioner might not be warranted due to occasional heat waves, an evaporative cooler provides a convenient solution. It can be easily rolled out of storage when needed, offering relief during periods of unexpectedly high temperatures without the hassle and expense of installing a traditional AC unit.

Moreover, coolers offer a unique advantage over air conditioners: they can effectively cool large open spaces and even outdoor areas. Unlike air conditioners, which primarily cool sealed rooms by removing heat, evaporative coolers lower the temperature of the air passing through them. This makes them suitable for use in cavernous factories, warehouses, outdoor restaurants, and amusement parks, especially as temperatures continue to rise. As such, these areas are expected to become growing markets for evaporative coolers.

The primary drawback of evaporative coolers is their inefficacy in humid conditions, akin to the limitations of sweating in high humidity, which is typical in a tropical monsoon climate like that in Vietnam. When the air is already saturated with moisture, water won’t evaporate off the pad, resulting in ineffective cooling. Instead, the device may function more like a fan, potentially making the room feel even muggier. However, in hot and less humid regions, evaporative coolers perform exceptionally well.

the world that we built

The widespread adoption of air conditioning led to building designs entirely reliant on artificial cooling.

Developers, eager to profit from cost-effective designs and maximize interior floor space that would have been unbearably hot in the past, opted for solid office blocks, glass towers, and boxy, mass-produced tract homes, all dependent on air conditioning for comfort. Traditional cooling methods such as courtyards, cross-ventilation, and other architectural features, have become a luxury, and a design choice rather than a necessity.

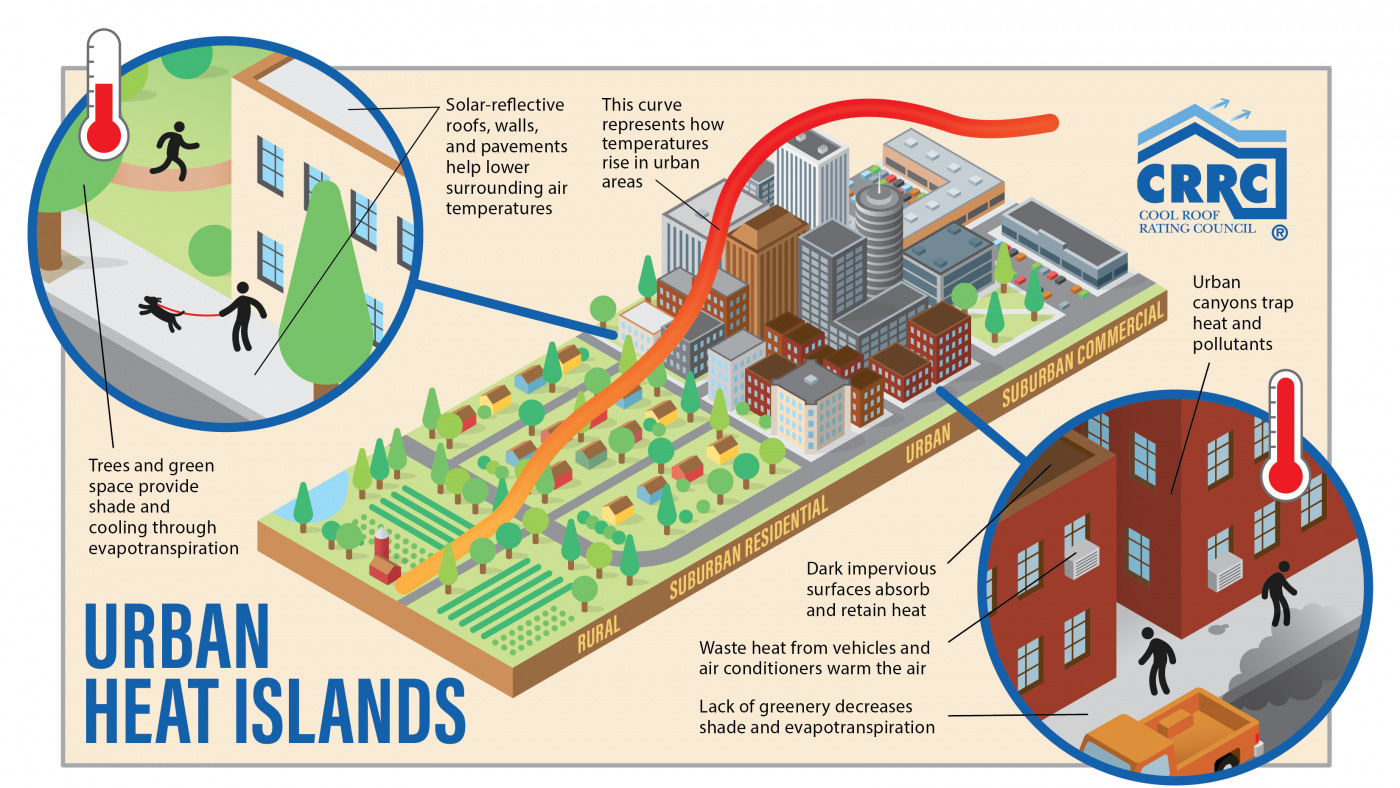

Concrete structures such as buildings, roads, and other infrastructure also absorb and re-emit the sun's heat more than natural landscapes such as forests and water bodies. Urban areas, where these structures are highly concentrated and greenery is limited, become “islands” of higher temperatures relative to outlying areas. The effect has earned its own name, urban heat island.

Today, we're paying a hefty price for that early pursuit of cheapness.

The magnitude of what cities must do to adapt to rising temperatures is daunting. Simply relying on individuals to acquire cooling appliances isn’t enough, as many would be left behind. While public health programs have saved countless lives, the increasing temperatures will necessitate more drastic measures to protect vulnerable populations.

As temperatures rise, you and I and the rest of the world will increasingly rely on air conditioners, adjusting our own lives and habits around them. Air-conditioned transit may become essential as biking on sweltering streets becomes impractical. Adjusting working hours to avoid the hottest parts of the day will become necessary, and new building designs will prioritize energy-efficient cooling systems. Perhaps buildings will even be prefabricated in cooled warehouses to minimize outdoor exposure. Additionally, personal cooling gear, such as cooling hardhats, may become commonplace.

Adapting to these challenges will be costly. With each degree of warming, the cost of maintaining a semblance of normal life will increase, leaving more people unable to afford it. The difficulty lies not in the impossibility of adaptation, but in ensuring equitable solutions that don't exacerbate the problem.

Addressing these challenges will require collective action, including international agreements like the Kigali Amendment, efficiency regulations, subsidies, technological advancements, new building designs, and civic programs. Planting more trees can help lower urban temperatures, while expanding mass transit can reduce the heat generated by internal combustion engines.

Moreover, new regulations will be needed to protect workers from heat-related illnesses, particularly in industries like construction. Cities may explore innovative solutions, such as shading entire intersections to provide shelter for vendors and traffic police from the sun.

Overall, adapting to the changing climate will require a comprehensive overhaul of infrastructure, technology, and policies. Piece by piece, through the adoption of new appliances and public works, cities will need to reconfigure themselves to thrive in a warming world.

Sài Gòn is starting its rain season. Now, it’s so easy to not remember that the world in which we live is getting warmer and warmer. Unless we do something about it.

We’re just 8 billion boiling frogs, with nowhere to jump out to.

Contribution of air conditioning adoption to future energy use under global warming | PNAS

Climate change has made air conditioning a vital necessity. It also heats up the planet. - Vox

Reminds me of a recent The Woke Salaryman post, but in the context of Singapore. We’re practically sacrificing for the next generation, as we’re just… doomed :)))

Personally, as a positive nihilist, I couldn’t care less about humankind - we’re all going to die anyway, and Earth can just wipe us all out for a fresh start.

so so insightful!!

sáng chị đọc bài này lúc vừa được đăng xong lật đật đi tắt máy lạnh :))) I know the negative effects AC have, but receiving reminders (especially those with rigorous research behind) now and then to stay mindful is very helpful!!